Fly Fishing the Gallatin River in Montana

Winter Fly Fishing on Montana’s Gallatin River

Those who say that fly fishing is a seasonal sport have clearly never been to Montana. The state’s inhabitants experience some of the harshest, coldest, windiest, and longest winters in the Lower 48, but diehard anglers rarely miss a chance to toss a fly around—even in mid-January.

As a kid, upon seeing a pair of fly fishermen trudging through a towering snowbank to reach the side of Montana’s Gallatin River, I worried for their health, safety, and—most of all—sanity. Once I caught the fly fishing bug, however, it no longer seemed such a bad idea. Eventually, and with some help from an experienced winter fly fisherman, I decided to give it a go.

Named by Meriwether Lewis in 1805 during the Lewis and Clark expedition, the Gallatin River winds through Wyoming and Montana for about 120 miles, converging with the Jefferson and Madison in Three Forks, MT to form the Missouri River. It served as the filming location of several scenes from A River Runs Through It, one of the greatest (and only) fly-fishing movies ever made.

During summer, the river is an enormously popular spot for fly fishing. In the shade of imposing canyon walls and tall evergreens, or bathed by the sun in mountain glades, anglers can wade into the Gallatin’s wide, cool waters to catch brown trout, rainbow trout, and whitefish. Stretches of the river have earned the coveted Blue Ribbon designation, indicating the highest quality of fishing.

During the winter, however, the crowds—a designation that in Montana means any group larger than 3 people—thin out. My first experience braving the cold with a fly rod came on a brisk morning in March, a month that, while representing spring in many parts of the country, rarely offers hints of a thaw in much of the Mountain West.

My guide and I had hopped in the truck in Bozeman, MT, less than an hour away from river access close to the highway in the Gallatin Canyon. On the ride over, he explained the primary enemy we would be facing—moisture.

In any winter sport or activity, it’s not necessarily the cold that poses the greatest risk, rather it’s the interaction between cold, wind, and especially moisture—an evident problem when you are going to be wading into a river. Much of that danger can come from the outside environment in the form of snow, ice, and of course water, but no matter how hard you try to keep the water out, your body is also constantly producing moisture in the form of sweat.

The trick, my guide explained, wasn’t to dress as warmly as possible by piling on huge winter coats. It was to use layers to maintain a relatively moderate level of warmth, enough to keep you comfortable but not enough to make you sweat.

Once on the river, however, fear of the cold immediately dissipated. The sun, reflected by the white snow, provided a brilliance that seemed to warm us from head to toe, despite the fact that the truck’s outdoor temperature monitor reported a meager 2 degrees Fahrenheit. Only my fingers, which I left mostly exposed, began to feel a little nippy.

When water temperatures drop, so too do the metabolisms of the fish, and therefore saving energy is of paramount importance for their survival. As a result, they tend to hang out close to the riverbed in slow-moving stretches of water where they will meet little resistance. Fish will rarely go very far out of their way to take a fly, so an angler will have to drop it right in front of their face. Double nymphing is therefore the best tactic, although there are days when dry flies can be effective.

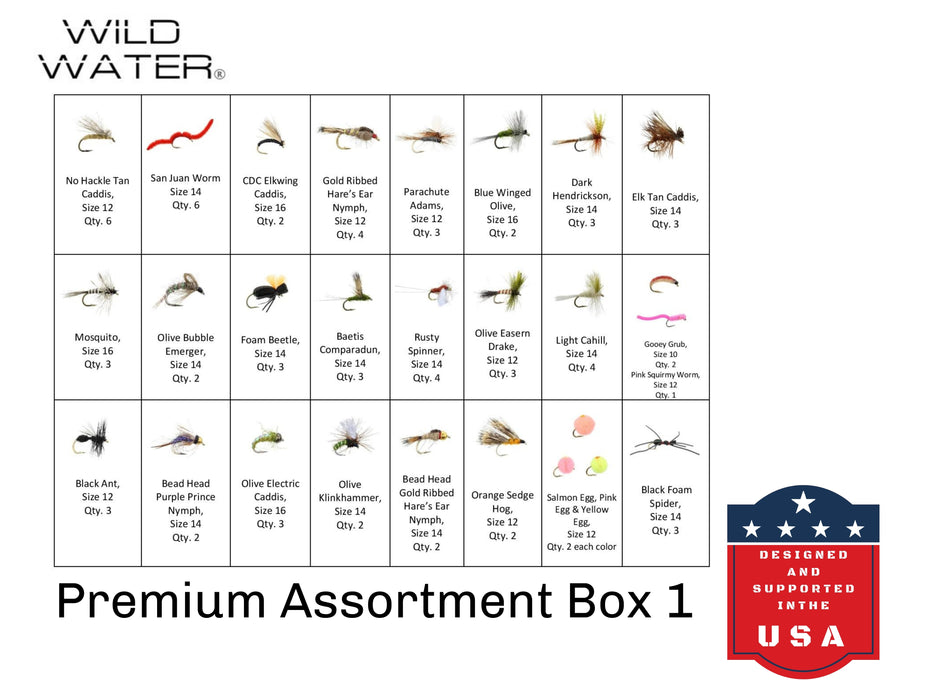

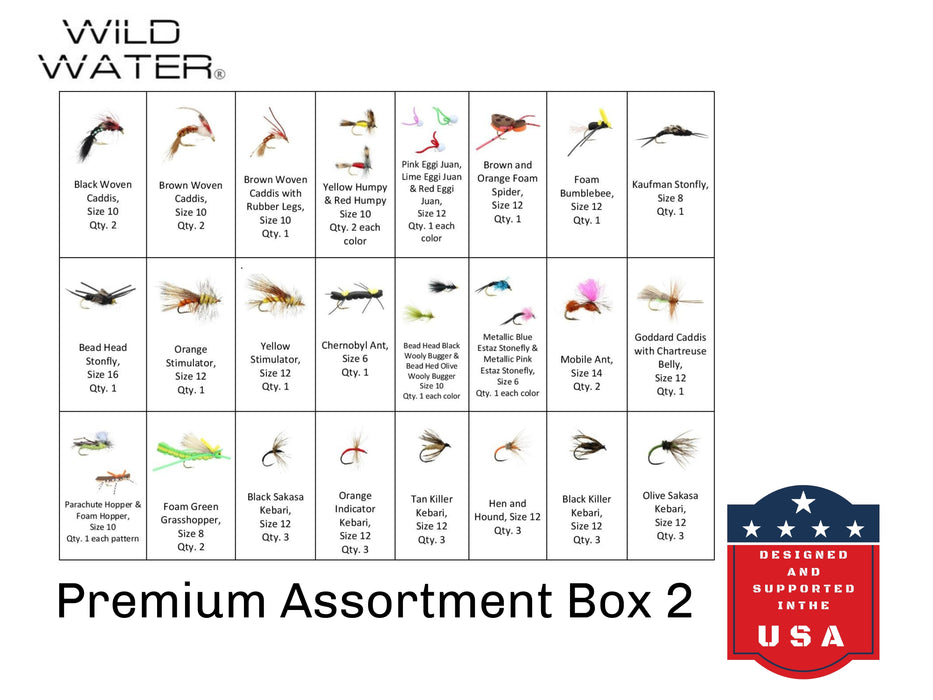

I let the guide pick out my flies—two nymphs—and was surprised to find that the selection wasn’t so different from what I might use in the summer months: stoneflies, caddis, mayflies, and midges. Below an indicator and some split shot weights, I tied on a stonefly and beaded san juan worm heavy enough to descend to the lowest depths, both de-barbed for the benefit of the fish.

After experimenting with various depths, the duo of flies created a combination that was richly rewarded. The placid water made it easy for me to see the strike indicator, which had several occasions to bob as various fish seized what I had to offer. It seemed that brown trout were my biggest customers of the morning, several measuring close to 20 inches. We seldom had to move spots, as the fish’s general laziness meant that we had to systematically work over each hole in order to cover the whole area.

Despite the cold, some fish had real fight in them, resulting in protracted battles and more than a few lost flies. It was important, the guide told me, to return them as quickly as possible, a task that proved complicated by my numb fingertips struggling to get hold of the hook.

By early afternoon, a new adversary appeared, and it was one we could not hope to beat: wind. The canyon, acting as a wind tunnel, channeled gusts of air that at best made casting difficult and, at worst, turned the complicated double-nymph rig into a tangled mess unparalleled since the days of Gordion’s knot. Despite putting on my last remaining layer, the convection currents of frigid air were too much for me to cope with, so we beat a quick retreat to the truck. A look at my weather app showed that the wind chill dipped well below 0, a final confirmation of what we both knew to be true; it was time to go home.