Oregon fly fishing hits its stride from September through December when the state's rivers deliver the best fly fishing of the year. This is the season when everything comes together.

From Central Oregon's high-desert canyons on the Deschutes to Southern Oregon's legendary salmon and steelhead rivers, the state offers excellent fishing for outdoor enthusiasts chasing trophy fish or families looking to hook their first trout.

This guide covers eight of Oregon's top fall destinations, month-by-month timing for each species, the flies that produce in autumn conditions, and what you need to know about licenses and regulations. But let's start with the best time to fly fish in Oregon during the season.

When to Fish: Oregon's Fall Calendar (September–December)

The table below breaks down what's happening each month so you can plan your fishing trip around peak activity. Keep an eye on river flows too. When autumn rains finally arrive, salmon and steelhead migrate upstream in waves. The best fishing often happens three to five days after a good rain when water levels drop and clarity returns.

| Month | What's Happening | Top Rivers |

|---|---|---|

| September | Summer steelhead peak, early chinook enter coastal rivers, October caddis hatches begin | Deschutes, McKenzie, Rogue |

| October | Fall chinook fishing peaks after first rain, steelhead spread throughout systems, October caddis in full swing | Nestucca, Clackamas, McKenzie |

| November | Late chinook, coho on north coast, early winter steelhead arrive | Nestucca, Rogue, Clackamas |

| December | Winter steelhead runs build, tailwater trout fishing stays productive | North Umpqua, Crooked River |

Once December hits, you're transitioning into winter steelhead season, which is a whole different game with bigger fish and colder fingers.

The Best Oregon Rivers for Fall Fly Fishing

The eight rivers below represent the best fall opportunities across the state. Some are famous. Others fly under the radar. All of them fish well from September through December when you time it right.

1. Deschutes River: Premier Fall Steelhead

- Best access: Maupin for walk-and-wade, Macks Canyon for boat-access water below

- Peak timing: Mid-September through November

- Top flies: Green Butt Skunk (sizes 4–8), Intruder in black or purple (sizes 2–4), October Caddis (sizes 6–10)

The Deschutes River is one of Oregon's defining steelhead destinations, and fall is when it shines brightest. This high-desert river carves through Deschutes National Forest before joining the Columbia, delivering 5,000 to 15,000 summer steelhead annually between July and December. By September, fish have spread throughout the system and stacked into the classic holding water that makes this place special.

What sets the Deschutes apart is the experience itself. For one, the lower 100 miles are fly-fishing only with no fishing from boats allowed. That means walk-and-wade water where you earn every grab.

When you start fishing, expect to catch an average of six to ten pounds per fish with the occasional trophy pushing well beyond that. The Deschutes also holds resident rainbow trout throughout, so bring a Steelhead Fly Assortment and a lighter rod for backup action when steelhead aren't cooperating. Swinging streamers through the tailouts works well for both species. Learn more about fishing with streamers if you're new to the technique.

For anglers new to spey casting or those unfamiliar with the water, local outfitters like Fly Fisher's Place in Bend offer guided fishing trips. All these help make your Oregon fly fishing trip one of a kind.

Central Oregon's weather cooperates in fall too, which add to the adventure. Expect crisp mornings, comfortable afternoons, and fewer crowds than summer.

2. Fall River: Spring Creek Dry Fly Fishing

- Best access: Fall River Campground off Highway 42

- Peak timing: September through October for dry fly action

- Top flies: October Caddis (sizes 8–12), Blue-Winged Olive (sizes 18–22), Parachute Adams (sizes 14–18)

Fall River is a different animal entirely. This pristine spring creek bubbles up from Cascade springs near Sunriver and flows just 12 miles before joining the Deschutes. The water runs cold and clear year-round, holding wild rainbow trout, brown trout, and brook trout that have seen plenty of flies and aren't easily fooled.

Fall brings October caddis and Blue-Winged Olive hatches that get fish looking up. When the hatch is on, you'll see noses poking through the surface in the slick water between weed beds. This is technical fishing that rewards patience and precise presentations. Heavy tippets and sloppy casts will get you nowhere.

In this case, a quality Dry Fly Assortment covers most situations here. Keep your leaders long and your expectations realistic. Rainbow average 10 to 14 inches, but the setting and the challenge make every fish feel earned. Brush up knowledge on fishing with a dry fly to make your Fall River trip worth it.

3. Crooked River: Tailwater Trout Year-Round

- Best access: Chimney Rock area, Castle Rock Campground

- Peak timing: Fall through spring (summer irrigation raises flows)

- Top flies: Zebra Midge (sizes 18–22), Pheasant Tail Nymph (sizes 16–20), Blue-Winged Olive (sizes 18–22)

The Crooked River below Bowman Dam is Central Oregon's most accessible year-round trout fishing. This tailwater stream holds plenty of trout, including native redband trout and stocked rainbow trout averaging 10 to 14 inches. The best trout push 20 inches and hang in the deeper runs where most anglers don't bother to look.

Fall delivers excellent fishing as irrigation releases decrease and flows stabilize, bringing fish to the surface when conditions cooperate.

But let's be honest. Most days you'll do better dead-drifting small nymphs along the bottom.

Sizes 18 to 22 in your standard attractor patterns produce consistently. So, stock up on small stuff with our Nymph Fly Assortment before you go. And if you're rusty on subsurface techniques, brush up on fishing with nymphs to make the most of your time.

When it comes to getting to the Crooked River, access couldn't be simpler. Highway 27 runs right along the river through Prineville, so you can pull off at a dozen different spots, rig up, and start fishing within minutes. No boats. No backcountry hiking. Just reliable trout water that doesn't require an expedition to reach.

4. Nestucca River: Coastal Fall Chinook

- Best access: Pacific City, Beaver, Blaine Road

- Peak timing: October through November after first rain

- Top flies: Egg patterns in chartreuse and pink (sizes 8–12), Egg-Sucking Leech (sizes 4–6), Clouser Minnow in chartreuse and white (sizes 2–4)

The Nestucca River near Pacific City ranks among the Oregon Coast's most consistent fall chinook producers. When autumn rains finally arrive and river flows rise, fresh chinook migrate upstream from the Pacific in impressive numbers. These are big fish too, averaging 20 to 30 pounds with trophies pushing well beyond 40.

The river also delivers early winter steelhead by late November, extending fishing opportunities into December for those willing to brave the coastal weather. Pack rain gear. You'll need it.

Bringing a solid selection of Salmon Flies doesn't hurt as well. It covers the essentials for coastal salmon fishing.

With that out of the way, let's talk about the most important thing with coastal rivers: timing.

In Nestucca's case, it responds dramatically to rain, sometimes blowing out completely before dropping back into shape. So when significant rainfall happen, you must plan your trip three to five days after the fact for the water to clear to that productive green tint. Show up during a flood or a drought and you'll be staring at empty water wondering what went wrong.

5. Clackamas River: Portland's Backyard Steelhead

- Best access: McIver State Park, Barton Park, Carver

- Peak timing: October for late summer fish, December for early winter fish

- Top flies: Intruder patterns (sizes 2–4), Egg-Sucking Leech (sizes 4–6), Pink Pollywog for coho (sizes 4–6)

The Clackamas River puts quality steelhead water within 30 minutes of downtown Portland. This Willamette tributary holds summer steelhead through October and delivers early winter steelhead by December. Fall also brings coho salmon that respond aggressively to swung flies.

McIver State Park and Barton Park offer the best public access. The trade-off, however, is pressure. You won't fish alone on weekends. But the fish are there, and weekday mornings reward early risers with quieter water.

Once you find a run to yourself, the Clackamas fishes well with traditional swing techniques. Work the tailouts methodically, keep your fly in the water, and cover ground until you connect.

A Steelhead Fly Fishing Kit gives you everything needed to get started on water like this.

6. McKenzie River: October Caddis and Wild Trout

- Best access: Vida, Blue River, McKenzie Bridge

- Peak timing: September through October for October caddis

- Top flies: October Caddis in tan and orange (sizes 6–10), Elk Hair Caddis (sizes 12–16), Stimulator (sizes 8–12)

The McKenzie River is one of Oregon's most celebrated trout waters and arguably the best fly fishing destination for fall dry fly action.

This Cascade Mountain stream flows through old-growth forest east of Eugene, holding plenty of trout that have made the river famous for generations. Wild "redside" rainbow trout average 12 to 16 inches here, with the best trout exceeding 20 inches.

Fall also brings the legendary October caddis hatch, and that's when things get exciting. These large orange caddisflies emerge in late afternoon (ideally the last two hours of daylight), triggering excellent fishing as aggressive fish smash dry flies in the fading light. There's nothing subtle about it. Trout that ignored your nymphs all day suddenly lose their minds over a size eight caddis pattern skittering across the surface.

It goes without saying, but you MUST stock up on Caddis Fly Patterns before your trip. And if you're unsure what to tie on when you get there, selecting the right fly breaks down the decision-making process.

7. Rogue River: Multi-Species Fall Action

- Best access: Grants Pass, Gold Beach, Galice

- Peak timing: September for summer steelhead, October through November for fall chinook

- Top flies: Egg patterns (sizes 8–12), Boss (sizes 4–6), Clouser Minnow (sizes 2–4)

The Rogue River in Southern Oregon offers the state's most diverse fall fishing opportunities. This wild and scenic stream flows 215 miles from Crater Lake to Gold Beach, attracting anglers chasing legendary salmon runs that have defined the region for over a century.

Aside from Summer steelhead and Fall chinook during the early to mid-portion of the season, coho salmon also join the mix as the season progresses.

Multi-day float fishing trips through the wilderness section deliver backcountry adventure with multi-species action. You'll camp on gravel bars, cook over open fires, and fish water that hasn't seen another angler in days. It's the kind of trip that reminds you why you started fly fishing in the first place.

For day trips, the water upstream from Grants Pass fishes well for steelhead through early fall. Half-pounder steelhead (immature fish running two to four pounds) provide fast-paced action when larger chinook aren't cooperating. They're scrappy, aggressive, and plentiful. And to match their intensity, you need a Salmon Fly Fishing Kit for the full Rogue experience.

Oregon Fishing License Requirements

Before you hit the water, you need the right paperwork. Oregon requires all anglers 12 and older to purchase a fishing license. If you're targeting steelhead or salmon, you'll also need a Combined Angler Tag on top of the base license.

Resident anglers pay $44 for the annual license plus $33.50 for the tag. Non-residents pay $98.50 plus $93.50. If you're just visiting for a long weekend, the one-day license at $21.75 includes the tag and keeps things simple.

One rule you absolutely need to know: wild steelhead fall under catch-and-release regulations on most rivers. You can identify wild fish by their intact adipose fin. Hatchery fish have the fin clipped and can be retained where regulations allow. Clip a wild fish and you're breaking the law, so learn to tell the difference before you start fishing.

Check the ODFW website for current regulations before your trip. Rules change by river and season, and ignorance isn't an excuse that holds up with a game warden.

Fall Fly Fishing in Oregon FAQs

What is the best month for fall fly fishing in Oregon?

October delivers the best combination of species and conditions. Steelhead have spread throughout the river systems, fall chinook fishing peaks after the first rain, and October caddis hatches drive aggressive trout feeding on rivers like the McKenzie. The weather is comfortable, the crowds have thinned, and rainbow trout are putting on weight before winter.

What flies should I bring for fall Oregon fishing?

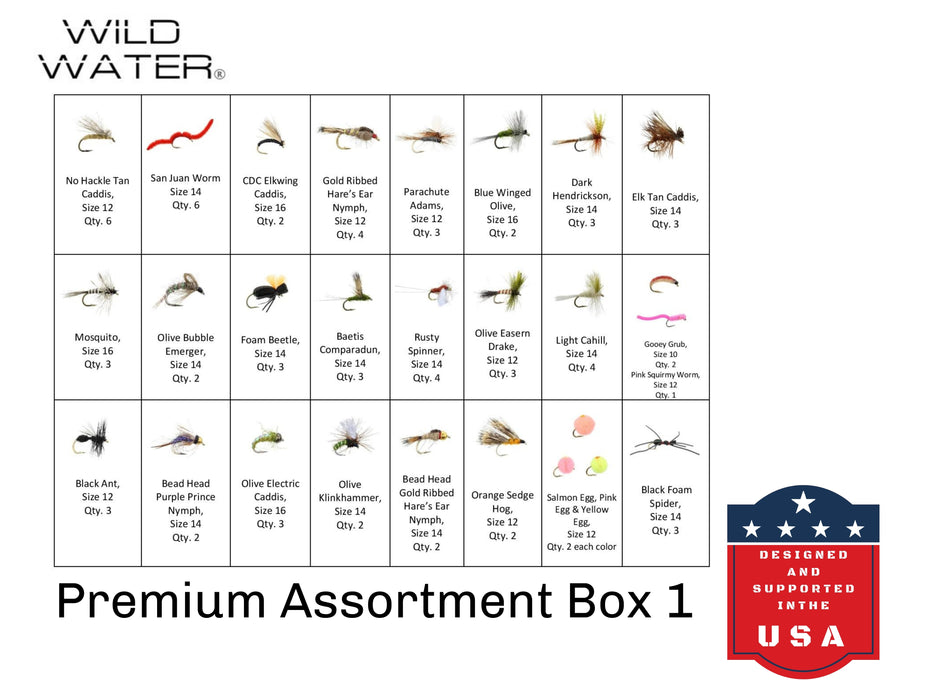

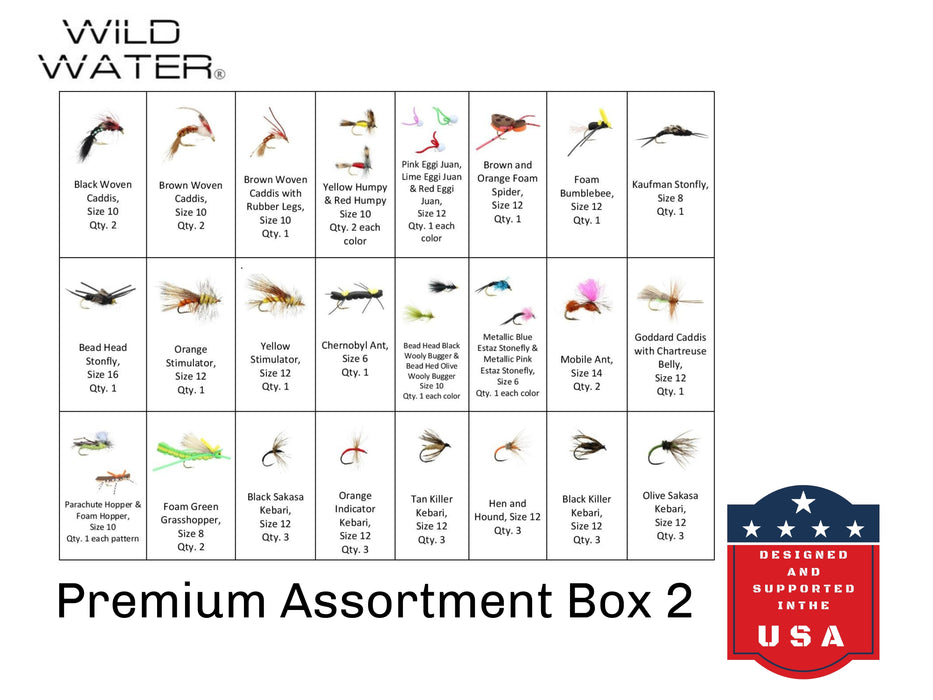

Pack Green Butt Skunks and Intruders for steelhead, chartreuse egg patterns for salmon, and October Caddis dries for trout. Add some Pheasant Tail nymphs in smaller sizes for tailwater fishing. A box of 20 to 30 flies covering these patterns handles most fall situations.

Can I keep wild steelhead in Oregon?

No. Wild steelhead with an intact adipose fin must be released under catch-and-release regulations. Only hatchery fish with a clipped fin can be retained, and bag limits vary by river. Check current regulations before you fish.

Is the Deschutes River fly fishing only?

Yes. The lower 100 miles of the Deschutes River are restricted to fly fishing with barbless hooks. No fishing from floating watercraft is allowed either, which creates the walk-and-wade experience the river is famous for.

When do fall chinook run in Oregon coastal rivers?

Fall chinook begin entering coastal rivers in September, but fishing doesn't peak until October or November after significant rain. When river levels rise, fresh salmon migrate upstream in waves. Time your trip three to five days after a good rain for the best shot at fresh fish.

Get on the Water This Fall

Oregon's fall season rewards anglers who do their homework. At this point, you have an idea which river to go. Now, study the regulations for each river before you go. Also, steelhead and salmon rules vary by water, and wild fish restrictions change throughout the season. It won't hurt to check current flows and conditions as well through ODFW's resources, then match your timing to the species you want to target.

If you're new to steelhead or salmon fishing, start with a guided trip on the Deschutes or Rogue. One day with a knowledgeable guide teaches you more than a season of trial and error. After that, you'll have the confidence to tackle these rivers on your own.

Of course, browse our Steelhead Fly Fishing Kits, Salmon Fly Fishing Kits, and Trout Fly Fishing Kits to find everything you need for Oregon's fall runs.