Coastal Fly Fishing for Stripers in Rhode Island

RHODE ISLAND FLY FISHING

For being the smallest state in the country, Rhode Island offers quite a bit of fishing. The Ocean State covers just over 1,000 square miles but has more than 400 miles of coastline. This is due to Narragansett Bay covering a good portion of the state. Narragansett Bay is an important resource for Rhode Island. It has been a significant shipping route for the last few centuries and supports various populations of fish and wildlife. It is best known for the clams that live on its floor, used in New England clam chowder. There are many islands in the bay, the biggest being Aquidneck Island, which was originally named Rhode Island. The name was changed back to the native name to avoid confusion. Narragansett Bay lies on the Eastern side of the state where elevations do not exceed 200 feet. The western side holds hills and forests that rise to 800 ft. The forests are a mixture of hardwoods and conifers. Reservoirs and ponds are scattered throughout, and rivers flow into Rhode Island’s coastline from higher elevations in the bordering states of Massachusetts and Connecticut. Block Island lies a few miles off the coast and is also part of Rhode Island. With the second highest population density in the country, much of the state is developed. Tourism is one of Rhode Island’s leading industries.

Summer temperatures are moderated by the Atlantic Ocean, averaging around 70 degrees with high humidity. The northern latitude gives Rhode Island colder winters, with average temperatures around 30 degrees. Weather is variable, and tropical storms & hurricanes can hit Rhode Island as they travel up the east coast.

The coastal ecosystem supports bird life including green & blue herons, warblers, and a variety of waterfowl. Sea ducks such as eiders and harlequin can be seen at certain times of year. Largemouth bass, pickerel, and other warmwater species live in the freshwater lakes and reservoirs. Popular saltwater species to fish for include bluefish, black sea bass, striped bass, and flounder.

Growing up, I was fortunate enough to know a family that kept a fishing boat on the coast. They invited me for a 3-day trip one summer. The plan was to fish the Block Island Sound for several species using different techniques. The first day, we trolled the coastline with traditional gear, catching bluefish and sea robins. Sea robins make a croaking noise like a bird when you put them on the deck of the boat. The next day, we slept in with the plan of fishing during the night. We headed out in the evening on the 24-foot Boston Whaler until the depth finder read 150-feet. Here, we dropped bait to the bottom and caught a few sand sharks, also known as dogfish. It was the hardest fighting fish I can remember reeling in. Around 10:00pm, we headed back into the shallows. It was high tide, and there were a few sandbars that my friend’s dad knew about where striped bass were laying.

Striped bass, or “stripers”, are a prized fish for fly anglers. They are an anadromous fish, just like salmon and steelhead. Stripers are born in fresh or brackish water and will live in river deltas or estuaries for their first few years of life. When they mature, they migrate out to the ocean. They travel up and down the Atlantic coast seasonally. When it comes time to spawn, they will migrate into fresh water. Anglers typically target these times, as fish will be concentrated at the mouths of rivers or in the rivers themselves. Stripers live up to 30 years and can reach up to five feet long.

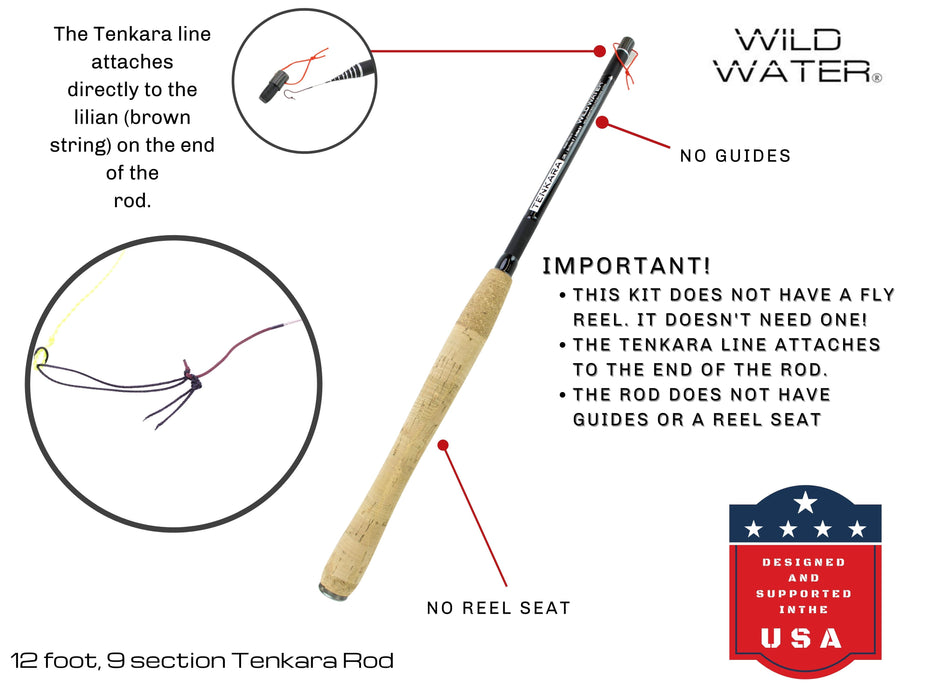

When we arrived at the sandbars, they were submerged under about 10 feet of water. Stripers target these areas to feet because they can corner baitfish in the shallows or near structure. Under the glare of the moonlight, we saw a frenzy of activity just beneath the water surface. Sure enough, the stripers had found a school of baitfish. My friend’s dad handed me a 9-foot 9-weight rod. It had floating line with a shooting head on it. The shooting head is a section of fly line on the front end that is significantly heavier and allows the angler to make a farther cast. At the end of the line was a 6-foot, 20-pound leader with a popper. This popper was a combination of rigid foam with a marabou tail, all white. He instructed me to cast into the middle of the feeding pod of fish, lower the rod tip, and strip the line. At my younger age, making a 50 foot cast with a 9-weight rod was a little too much, so he helped me out. I began stripping the line hard and fast, rhythmically. Poppers sit on the surface of the water and create a large disturbance as they’re pulled in, attracting the fish. It didn’t take long before there was an explosion on the surface, and I do mean explosion. The popper disappeared as the entire body of a 25 inch striper came out of the water. Setting the hook wasn’t necessary, as this fish was so aggressive that it did all the work for me. I remember holding on to that fly rod for dear life as the striper pulled. Luckily, landing fish in saltwater offers less challenges as there is much more open water for them to run and less structure for them to tangle the line around. After an intense five minute fight we managed to net the fish. It was another significant experience in my childhood that helped fortify my addiction to fly fishing. For those that haven’t experienced saltwater fly fishing, add it to your list because it can be the thrill of a lifetime.