Most anglers have never heard of the Tongue River. That's exactly why you should fish it.

This guide covers everything you need to plan your Tongue River fishing trip. You'll find access points, regulations for each fork, seasonal hatch timing, and the flies that actually work on this water. Let's begin with the different species of trout in the river.

Tongue River Trout Species

The Tongue River offers four trout species, and each one fights like it has something to prove.

- Rainbow trout run 10 to 22 inches and make up the bulk of what you'll catch. They're not picky eaters during a hatch, but they'll humble you in the gin-clear water when nothing's coming off.

- Brown trout range from 8 to 18 inches and behave exactly like browns everywhere: paranoid, nocturnal, and absolutely worth the effort. Dawn and dusk are your windows. The rest of the day, they're watching you from under cut banks, judging your cast.

- Cutthroat trout enter the mix courtesy of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, which stocks Snake River cutthroat annually in the North Fork's restricted harvest area. These fish display the distinctive red-orange slash marks under their jaw that give them their name. They're generally easier to fool than browns and fight with surprising strength for their size. Catch-and-release regulations protect them here, so handle them carefully and get them back in the water quickly.

- Brook trout are the river's scrappy underdogs. Brookies here average 6 to 14 inches, and what they lack in size they make up for in aggression. They'll slash at a fly before it hits the water. Fair warning: their teeth have ended many a tippet prematurely.

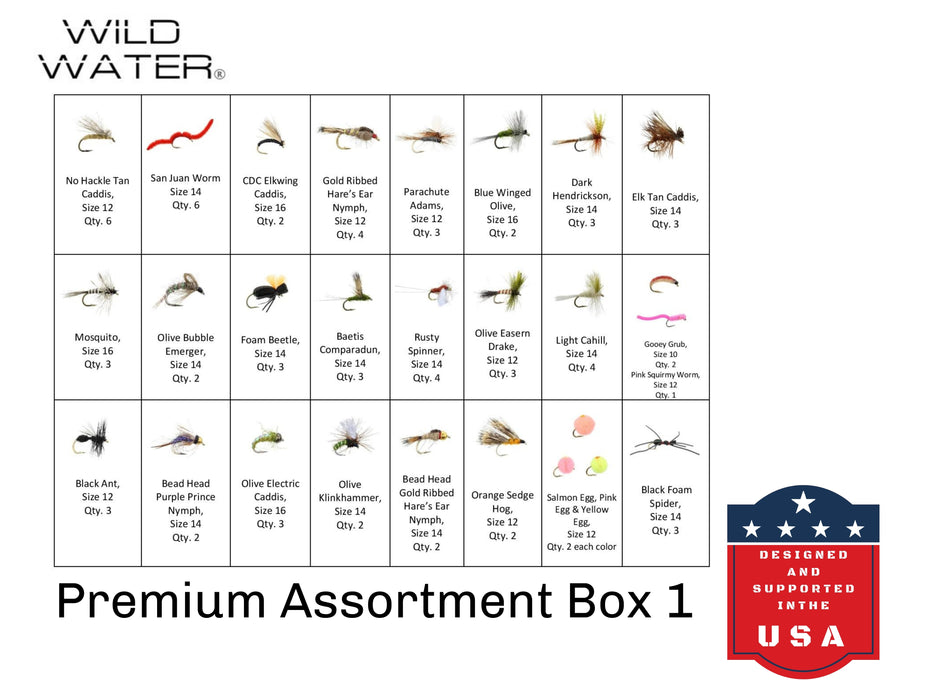

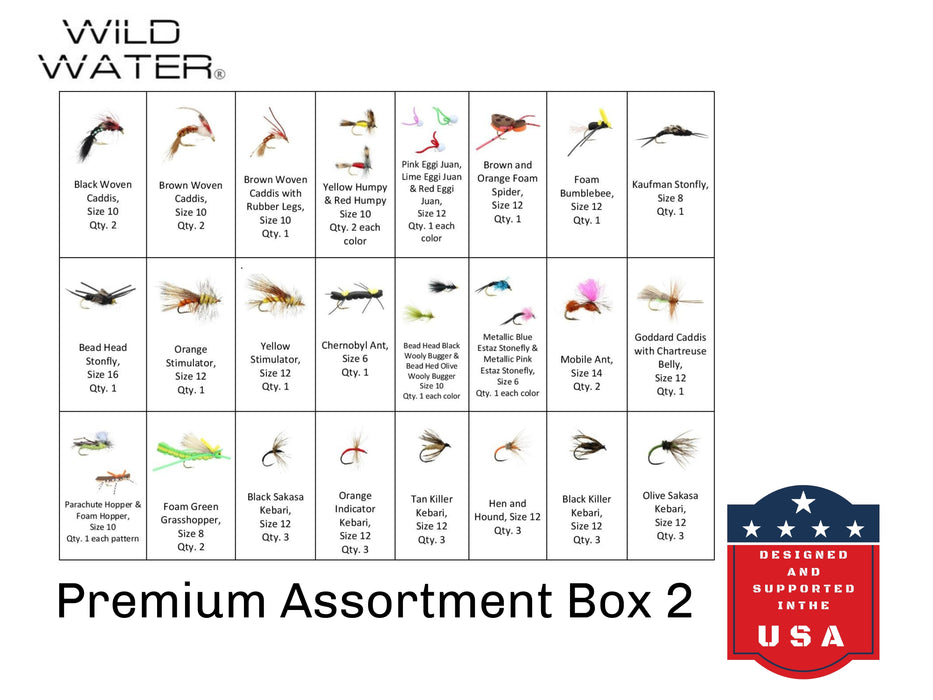

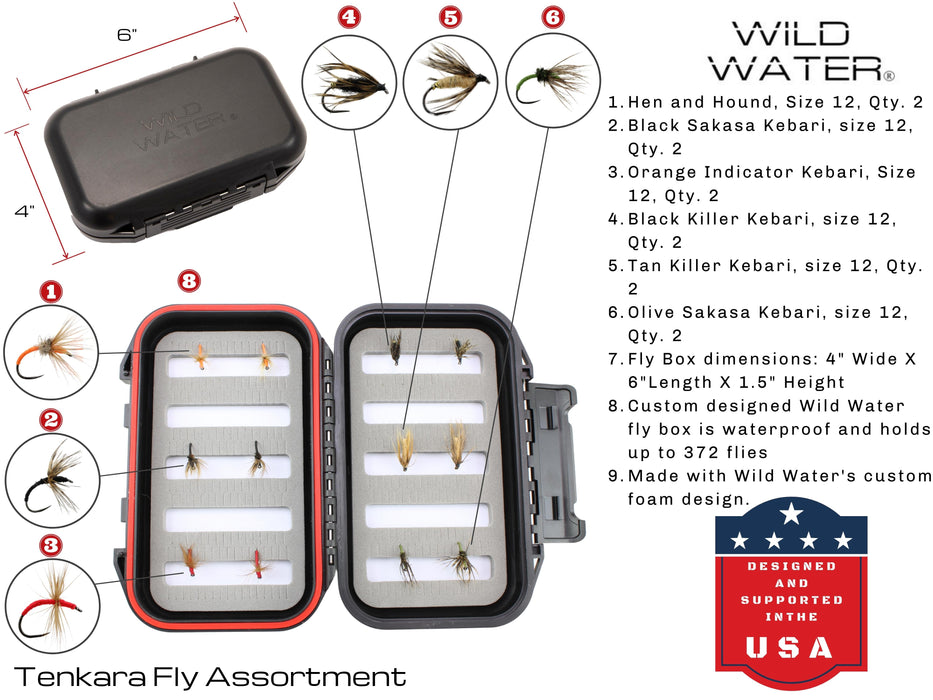

The South Fork's wild trout fishery produces 4,000 to 5,000 trout per mile, with 65 to 75 percent measuring over 6 inches. That's not a typo. This is all the more reason for you to stock your box with proven trout flies or grab a complete trout fly fishing kit if you're building your setup from scratch.

North Tongue River vs. South Tongue River

The Tongue River splits into two forks in the Bighorn National Forest, and choosing the right one depends on what kind of fishing experience you're after. Below is a brief breakdown of both for quick reference:

| North Tongue | South Tongue | |

|---|---|---|

| Character | Canyon to meadow | Pocket water, tighter |

| Regulations | Catch-and-release (except brookies), artificial only | Standard state regulations |

| Stocking | Snake River cutthroat annually | None since 1991 (wild fishery) |

| Access | Easier, highway-adjacent | More remote, rougher roads |

| Best for | Beginners, accessible wading | Solitude seekers, experienced anglers |

Let's now get in depth with each, starting with the North Tongue River. It carves through a dramatic canyon before opening into meadow stretches higher up. This is the more accessible fork, with Highway 14A running parallel for much of its length. On the downside, you might actually see other anglers here.

The North Fork falls under special regulations: all trout except brook trout must be released immediately, and you're limited to artificial flies and lures only. This applies to the entire North Tongue River drainage upstream from the mouth of Bull Creek in Sheridan County.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department stocks Snake River cutthroat here annually, which adds variety to the wild rainbow and brown trout populations.

The South Tongue River is where things get interesting. This fork has been managed as a wild trout fishery since 1991, meaning no stocking whatsoever. The result is a self-sustaining population of rainbow, brown, and brook trout that have never seen a hatchery.

Fish population estimates show 4,000 to 5,000 trout per mile, with the majority over 6 inches. The South Fork flows through tighter terrain with more pocket water and requires a bit more effort to reach, which keeps pressure low.

Both forks require a valid Wyoming fishing license. Non-resident licenses are available online through the Wyoming Game and Fish Department website. If you're new to reading trout water, brush up on how to identify holding lies and feeding lanes before you go. And if fly fishing itself is new territory, start with the complete beginner's guide to fly fishing to build your foundation.

How to Access the Tongue River

Getting to the Tongue River requires some planning, but nothing too complicated if you know where you're headed. All routes start from Sheridan, the main gateway town about 30 minutes east of the first access points.

Tongue River Canyon Access

From Sheridan, take Exit 9 off I-90 and head west on Highway 14 toward Dayton. Just before you cross the river at the edge of town, turn right onto Highway 343. Within about a mile, look for Tongue Canyon Road on your left. This road parallels the river to the Sheridan County Picnic Ground, where the Tongue Canyon Trail begins. Once you cross onto state lands, you can fish anywhere within the public access boundary.

The canyon section offers scenic water but limited backcast room in spots. If you're comfortable with tight quarters, the trout here see less pressure than the more open stretches upstream.

North Tongue River Access

For higher elevation water with more room to cast, continue past Dayton on Highway 14 to the junction with Highway 14A at Burgess Junction. The Bighorn National Forest maintains three fishing access points along this stretch.

From Dayton, take Highway 14 west for 27 miles to the Highway 14A junction, then continue 2 miles on 14A. Watch for Forest Service Road 174 on the north side of the highway. Elevation here sits around 8,100 feet, so dress in layers even in summer. Afternoon thunderstorms roll in fast at this altitude.

South Tongue River Access

The South Fork demands a bit more commitment to reach, which is precisely why the fishing stays good.

Take Highway 14 to Prune Creek Campground, then head south on Forest Development Road 193. You can also access it via FDR 26, fishing downstream from Dead Swede Campground. These roads require high-clearance vehicles, especially the last couple of miles where boulders and ruts will punish a sedan. Leave the low-clearance rental at the hotel and borrow a truck if you can.

The extra effort pays off. Fewer anglers make the trek, and the wild trout population here reflects that reduced pressure.

Camping Near the Tongue River

Once you've picked your water, you'll need a place to sleep. Options range from developed campgrounds to dispersed backcountry sites.

The Forest Service maintains several campgrounds in the Tongue drainage: North Tongue, Dead Swede, Owen Creek, Prune Creek, Sibley Lake, and Tie Flume. These offer basic amenities and easy river access. Dispersed camping is allowed outside riparian zones if you prefer solitude and don't mind roughing it.

The Tongue River Canyon Public Access Area offers eight designated campsites with fire pits, bear-proof food storage containers, and outhouses. There's a five-day camping limit, and popular sites fill quickly on summer weekends. Arrive Thursday if you want your pick.

A sturdy fly rod case is worth its weight on these rough forest roads.

When to Fish: Seasons and Hatches

The Tongue River fishes year-round, but timing your trip to match insect activity makes a significant difference in your catch rate.

Water temperatures in the upper Tongue run 45 to 55 degrees through summer thanks to glacier runoff from the Bighorn peaks. This keeps trout active and feeding throughout the day rather than retreating to deep pools like they do on warmer freestones. Each season brings different opportunities and challenges, so check out our guide on selecting the right fly to match your box to conditions.

Spring (April through May)

Ice typically clears by mid-April, signaling the start of the prime season.

Midge hatches kick things off, followed by the first Blue-Winged Olives of the year. Overcast days are your friend here. Fish rise steadily when cloud cover keeps light levels low. Flows run higher during snowmelt, so focus on slower edges and backwaters where trout can feed without fighting heavy current.

Wading can be tricky when runoff peaks, but the fish are hungry after a long winter and willing to forgive a sloppy presentation.

Summer (June through August)

Once flows stabilize in June, the Tongue River enters peak season.

Caddis hatches explode across the river, and the fishing gets as good as it gets anywhere in Wyoming. Evenings produce reliable dry fly action as these insects swarm the water. Stock up on caddis patterns before your trip.

By late July, terrestrials become a factor on the lower meadow stretches. Hoppers tumbling off grassy banks trigger explosive strikes from opportunistic trout.

This is also when you'll encounter the most company on the water. Weekdays fish noticeably quieter than weekends if your schedule allows flexibility.

Fall (September through October)

If you can only make one trip per year, fall deserves serious consideration.

After Labor Day, the crowds disappear and the fish get aggressive. Browns begin staging for their fall spawn, making them territorial and willing to chase larger offerings. BWO hatches return on gray afternoons, offering dry fly opportunities between subsurface sessions. The cottonwoods and aspens turn gold along the river, and morning frost adds a layer of solitude that summer anglers never experience.

Winter (November through March)

Winter fishing is possible but demands commitment.

Ice fishing draws a few hardy souls to the slower pools, though most anglers wait for spring. If you do venture out, target deeper water with small midges fished painfully slowly. Dress for conditions that can turn dangerous quickly at elevation, and check road conditions before heading up. Some forest roads close entirely once snow accumulates.

Best Flies and Gear for Tongue River Trout

You don't need a thousand patterns to fish the Tongue effectively. A focused selection built around proven producers will serve you better than a cluttered box. Below are what actually works on this water.

Dry Flies

Start with Elk Hair Caddis in sizes 14 to 16. This pattern should be your first choice when you see fish rising in the evening during summer months.

Add Parachute Adams (14 to 16) as an all-purpose searching pattern when you're not sure what's coming off. The white post makes it easy to track in riffled water. Blue-Winged Olives (16 to 18) round out your dry fly box for those overcast afternoons when mayflies blanket the surface.

Nymphs

When fish aren't looking up, they're eating subsurface. That's most of the time.

Pheasant Tail Nymphs (14 to 18) and Hare's Ear Nymphs (12 to 16) cover the majority of situations you'll encounter. Both imitate aquatic insects trout feed on year-round, and both have been fooling fish for generations.

Note: For technique guidance, read up on fishing with nymphs before your trip.

Streamers

Streamers earn their place when targeting larger, aggressive fish.

Woolly Buggers in black and olive (sizes 8 to 10) remain the standard for good reason. They imitate everything from leeches to baitfish to nothing in particular, and trout eat them anyway. Strip them through deeper pools at dawn and dusk for your best shot at the river's larger residents.

Terrestrials

Don't overlook terrestrial flies or the bugs that fall in from the banks. Hoppers, ants, and beetles produce well on the meadow stretches where grass grows right to the water's edge. Foam hopper patterns in sizes 8 to 10 draw explosive strikes from fish holding along grassy banks. There's nothing subtle about a trout eating a hopper.

Rod Selection

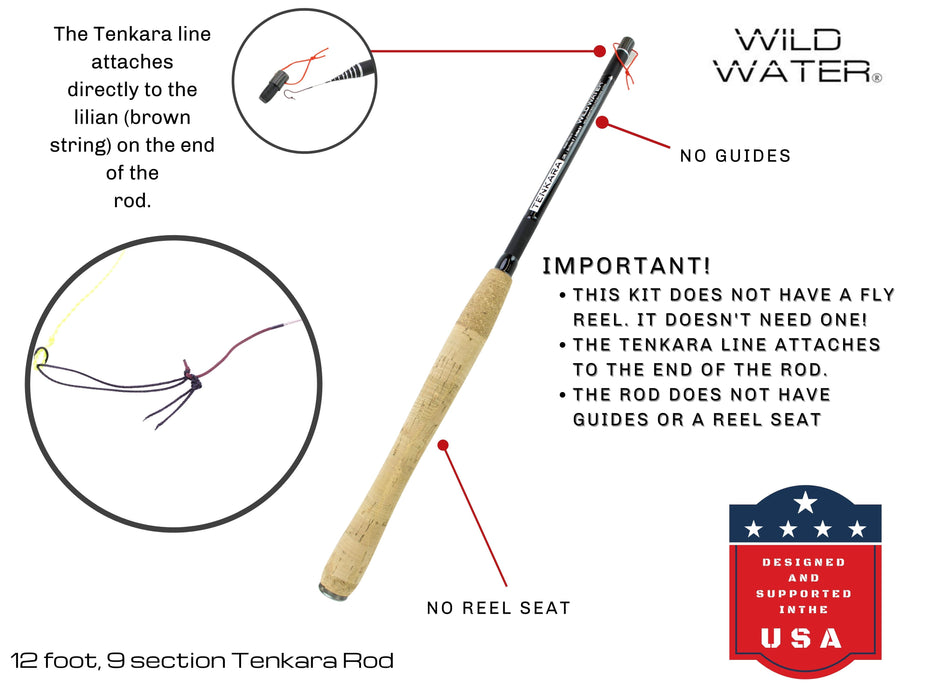

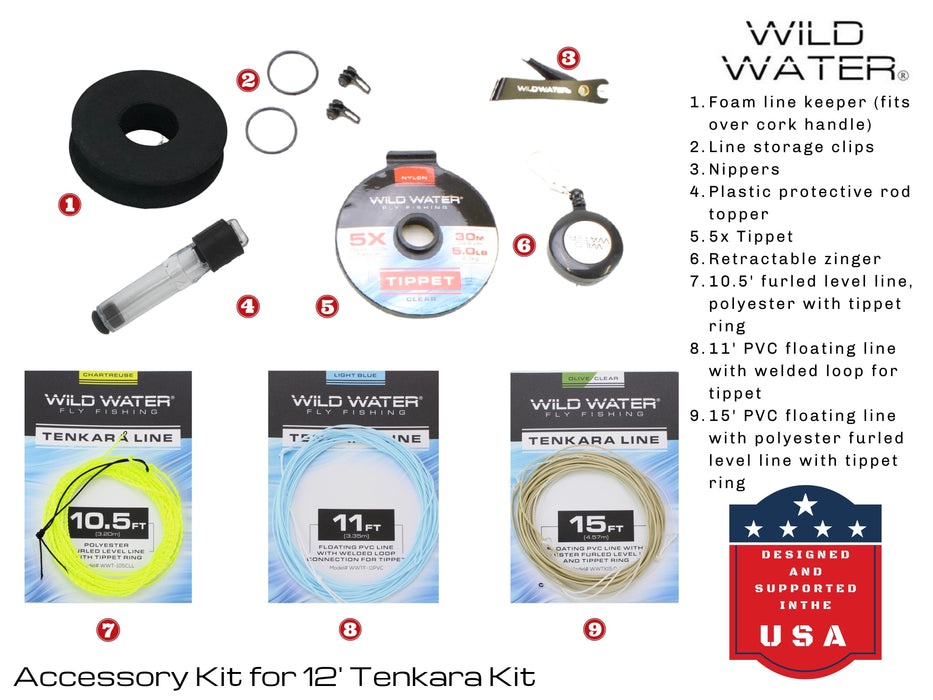

Since we've cleared the flies, let's now talk about rod, and your choice depends on the water you're targeting and the fish you expect to catch.

A 9-foot 5-weight handles most Tongue River situations with enough backbone for streamers and delicacy for dry flies. It's the workhorse choice. A 5-weight fly fishing kit sets you up with everything matched and ready to fish.

If you're focusing on the smaller pocket water of the South Fork or specifically targeting brookies, a 4-weight kit offers a more sporting experience and better feel for smaller fish.

Leaders and Tippet

Stock up on leaders and tippet before your trip. Options are limited once you're in the mountains, and running out mid-trip means a long drive back to Sheridan.

When choosing your terminal tackle, be wary that the Tongue runs crystal clear most of the season, which means trout have plenty of time to inspect your offering. This is why you must step down to 5X tippet for wary fish. Fluorocarbon helps when trout are being particularly fussy since it's nearly invisible underwater.

Tongue River Fishing FAQs

Do I need a fishing license for the Tongue River?

Yes. All anglers 14 and older need a valid Wyoming fishing license. Residents and non-residents can purchase licenses online through the Wyoming Game and Fish Department website. Prices and regulations change, so verify current requirements before your trip.

What are the catch-and-release rules?

The North Tongue River drainage upstream from Bull Creek is catch-and-release for all trout except brook trout, which you can harvest. Only artificial flies and lures are permitted in this section. The South Tongue follows standard statewide regulations. When in doubt, check the current Wyoming fishing regulations booklet or contact the Sheridan Regional Office at (307) 672-7418.

Are there dangerous animals on the Tongue River?

Moose are your primary concern. They frequent the river corridor and can be aggressive, especially cows with calves. Give them plenty of space and never position yourself between a cow and her calf. Black bears and mountain lions inhabit the area but encounters are rare. The Forest Service provides bear-proof food storage containers at designated campsites for a reason. Use them.

What flies should I bring if I can only pick five?

Elk Hair Caddis (size 14), Parachute Adams (size 16), Pheasant Tail Nymph (size 16), Hare's Ear Nymph (size 14), and a black Woolly Bugger (size 10). This lineup covers dry fly, nymph, and streamer fishing across all seasons. Add hoppers if you're visiting in late summer.

Start Planning Your Tongue River Trip

The Tongue River won't show up on most "best of" lists, and that's part of what makes it worth the drive. While other anglers line up shoulder to shoulder on famous tailwaters, you can have miles of wild trout water practically to yourself.

Whether you choose the accessible North Fork or the wilder South Fork, you'll find healthy populations of trout in pristine water with mountain scenery that rivals anywhere in the West. Bring the right flies, respect the regulations, and give the moose their space.

Your first Tongue River fish is waiting. Grab a fly fishing kit, stock your box with trout flies, and go find it.